Tlingit, Haida, Eyak & Tsimshian Culture

The Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and Eyak live throughout Alaska's southeastern panhandle — the Inside Passage region — sharing many cultural similarities with groups along the Pacific Northwest Coast, from Alaska through Canada all the way down to northwestern California.

The Haida (HIGH-duh) live on Prince of Wales Island as well as on Haida Gwaii in Canada. The Tlingit (CLINK-it) live throughout all of Southeast Alaska. The Tsimshian (SIM-shee-ann) people live primarily in Metlakatla, Alaska’s only reservation, and British Columbia, Canada. The Eyak (EE-yak) lived in the region around the eastern side of the Prince William Sound and the Copper River delta.

Southeast Alaska Native peoples are talented craftspeople. Intricate weaving techniques are used to create both functional and beautiful pieces — from baskets for cooking and storage to ceremonial robes, floor mats, and room dividers to clothing and hats. Their carving can be seen on totems and canoes, as well as utensils and ceremonial objects.

You can visit the Totem Heritage Center in Ketchikan to learn about traditional and modern carving techniques, and to see the craftsmanship of totems hundreds of years old. In Sitka, experience the drumming and hear traditional stories shared by the Sheet'ka Kwaan Naa Kahidi Dancers at the Sheet'ka Kwaan Naa Kahidi Community House. The Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau continues the arts, cultural, and language traditions of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples through workshops, classes, monumental art, and collections.

In Cordova, make sure to visit the Ilanka Cultural Center operated by the Native Village of Eyak which has a fully intact killer whale skeleton, as well as a small gift shop. You can visit Metlakatla via a guided tour leaving from Ketchikan or flight tours, but if you want to spend more than 24 hours on the island, you must apply for a visitor permit.

The Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and Eyak have inhabited Southeast Alaska for more than ten thousand years. Southeast Alaska's maritime environment provides plenty. Salmon and halibut, sea plants, berries, seals, moose, deer, and mountain goat remain important food sources today. The water supplies food and transportation, while wood from the tall trees of the temperate rainforest contributes housing and tools. The people of Southeast Alaska were accomplished boatmen and traders and built long canoes out of cedar for traveling.

Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and Eyak social systems are highly complex. Each of these groups is organized into two equal halves, the Eagle and Raven moieties, which consist of several clans each. The clans are matrilineal, meaning that children inherit through their mother. Traditionally, marriages were arranged between members of the opposite moiety.

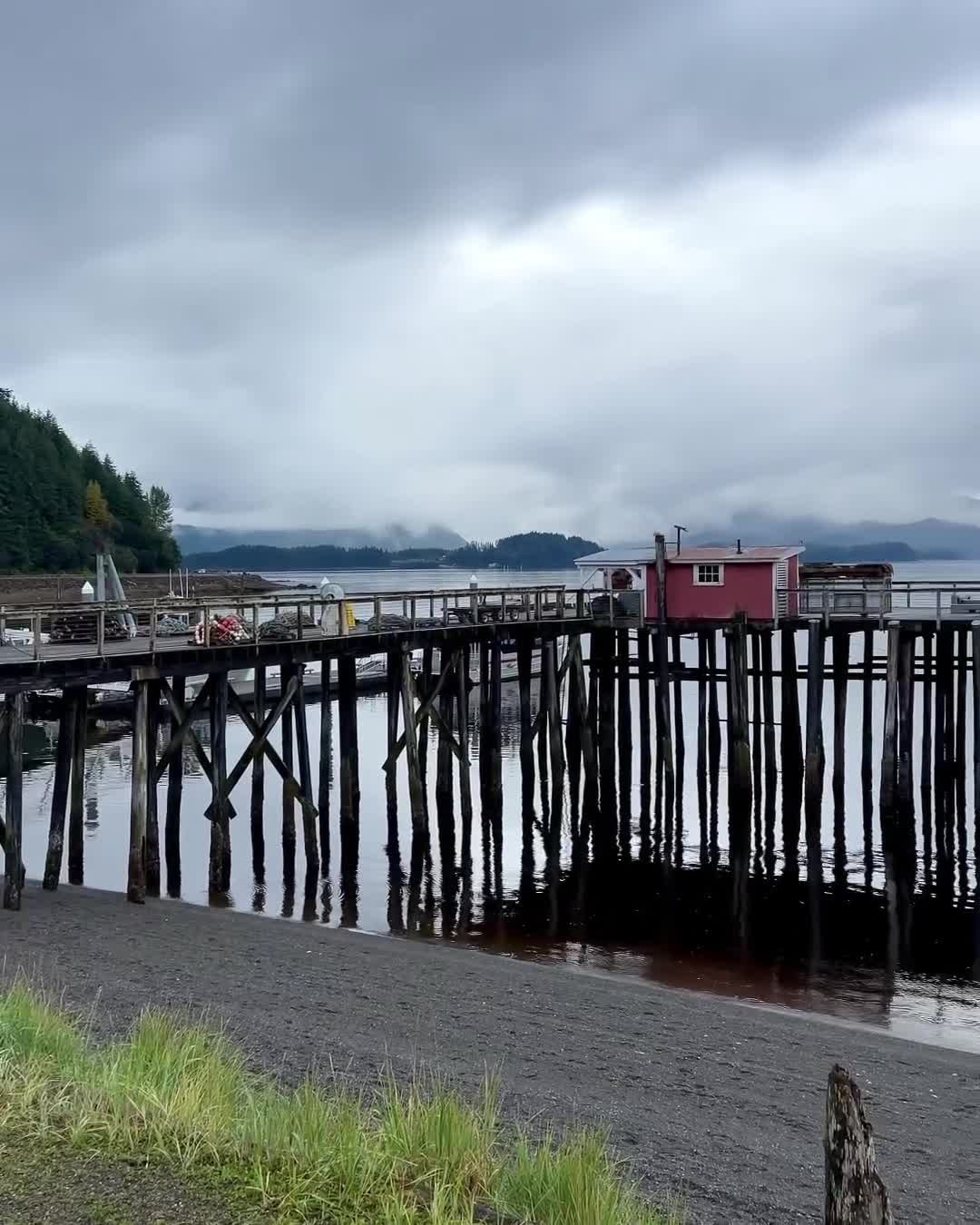

Southeast Alaska Native peoples built permanent winter settlements, usually a row of plank houses facing a river or saltwater beach. Each clan lived together, with up to 50 people in one house. Seasonal camps were built as needed, near sources of food and water.

Cultural Regions Map

Tlingit, Haida, Eyak & Tsimshian Traditions & History

From the Alaska CulturalHost Program

The Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian share a common and similar Northwest Coast Culture with important differences in language and clan system. Anthropologists use the term “Northwest Coast Culture” to define the Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian cultures, as well as that of other peoples indigenous to the Pacific coast, extending as far as northern Oregon. The Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian have a complex social system consisting of moieties, phratries, and clans. Eyak, Tlingit, and Haida divide themselves into moieties, while the Tsimshian divide into phratries.

The region from the Copper River Delta to the Southeast Panhandle is a temperate rainforest with precipitation ranging from 112 inches per year to almost 200 inches per year. Here, the people depended upon the ocean and rivers for their food and travel. Although these four groups are neighbors, their spoken languages were not mutually intelligible.

- Eyak is a single language with about 50 speakers, but no living fluent speakers remain

- The Tlingit language has four main dialects: Northern, Southern, Inland, and Gulf Coast with variations in accent from each village

- The Haida People speak an isolate (unrelated to other) language, Xaat Kíl, with three dialects: Skidegate and Masset in British Columbia, Canada, and the Kaigani dialect of Alaska

- The Tsimshian People speak another isolate language, Sm’algyax, which has four main dialects: Coast Tsimshian, Southern Tsimshian, Nisga’a, and Gitksan.

Eyak occupied the lands in the southeastern corner of Southcentral Alaska. Their territory runs along the Gulf of Alaska from the Copper River Delta to Icy Bay. Oral tradition tells us that the Eyak moved down from the Interior of Alaska via the Copper River or over the Bering Glacier. Until the 8th century, the Eyak were more closely associated with their Athabascan neighbors to the north than the North Coast Cultures.

Traditional Tlingit territory in Alaska includes the Southeast panhandle between Icy Bay in the north to the Dixon Entrance in the south. Tlingit People have also occupied the area to the east inside the Canadian border. This group is known as the “Inland Tlingit.” The Tlingits have occupied this territory for a very long time. The western scientific date is 10,000 years, or, Alaska

Native Peoples say, “since time immemorial.”

The original homeland of the Haida People is the Queen Charlotte Islands in British Columbia, Canada. Prior to contact with Europeans, a group migrated north to the Prince of Wales Island area within Alaska. This group is known as the Kaigani or Alaska Haidas. Today, the Kaigani Haida live mainly in two villages, Kasaan and the consolidated village of Hydaburg.

The original homeland of the Tsimshian is between the Nass and Skeena Rivers in British Columbia, Canada, though at contact in Southeast Alaska’s Portland Canal area, there were villages at Hyder and Halibut Bay. Presently in Alaska, the Tsimshian live mainly on Annette Island, in (New) Metlakatla, Alaska in addition to settlements in Canada.

HOUSE TYPES & SETTLEMENTS

Before and during early contact with the non-aboriginal population, the people built their homes from red cedar, spruce, and hemlock timber and planks. The houses, roofed with heavy cedar bark or spruce shingles, ranged in size from 35’-40’ x 50’-100’, with some Haida houses being 100’ x 75’. All houses had a central fire pit with a centrally located smoke hole. A plank shield framed the smoke hole in the roof. Generally, each house could hold 20-50 individuals with a village size between 300-500 people.

The people had winter villages along the banks of streams or along saltwater beaches for easy access to fish-producing streams. The location of winter villages gave protection from storms and enemies, drinking water and a place to land canoes. Houses always faced the water with the backs to the mountains or muskegs/swamps. Most villages had a single row of houses with the front of the house facing the water, but some had two or more rows of houses.

Each local group of Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian had at least one permanent winter village with various seasonal camps close to food resources. The houses held 20-50 people, usually of one main clan. In each Eyak village, there were two potlatch houses, outside of which was a post topped with an Eagle or Raven. The dwelling houses were unmarked. The southern Tlingit had tall totem poles in the front of their houses. The Northern Tlingit houses had fewer and shorter frontal totem poles.

TOOLS & TECHNOLOGY

Southeast Alaska’s environment is a temperate rainforest. This environment produces many tall and massive trees. Wood was the most important commodity for the people. Houses, totem poles, daily utensils, storage and cooking boxes, transportation, ceremonial objects, labrets (worn by high status women), and clothes all were made of wood and wood products. The tools to make the wood into usable items were adzes, mauls, wedges, digging sticks, and after contact, iron. To cut the wood, people used chipped rocks, bones, beaver teeth, and shells. For light, the Eyak used a clamshell with seal oil or pitch, and a lump of fat for a wick in the sleeping room. Dried hooligan were used as candles and hollowed sandstone with cotton grass were fashioned into wicks.

Various means were used to harvest the seasonal salmon runs. Fish weirs (fences) and traps were placed in streams. Holding ponds were built in the intertidal region. Dip nets, hooks, harpoons, and spears were also used to harvest salmon during the season. A specialized hook, shaped in a ‘V’ or ‘U’ form allowed the people to catch specific sized halibut.

Various baskets were used for cooking, storage, and for holding clams, berries, seaweed, and water. The Tsimshian used baskets in the process of making hooligan (a special smelt) oil. Basket weaving techniques were also used for mats, aprons, and hats. Mats woven of cedar bark were used as room dividers and floor mats, as well as to wrap the dead prior to burial or cremation. The inner cedar bark was pounded to make baby cradle padding, as well as clothing such as capes, skirts, shorts, and blankets (shawls). The Nass River Tsimshian are credited with originating the Chilkat weaving technique, which spread throughout the region.

SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

No central government existed. Each village and each clan house resolved its differences through traditional customs and practices; no organized gatherings for discussions of national policy making took place. Decisions were made at the clan, village or house level, affecting clan members of an individual village or house. The people had a highly stratified society, consisting of high-ranking individuals/families, commoners, and slaves. Unlike present day marriages, unions were arranged by family members. Slaves were usually captives from war raids on other villages.

All four groups had an exogamous (meaning they married outside of their own group), matrilineal clan system, which meant that the children traced their lineage and names from their mother (not their father as in the European system). Therefore, the children inherit all rights through the mother, including the use of the clan fishing, hunting, and gathering land, and the right to use specific clan crests as designs on totem poles, houses, clothing, and ceremonial regalia.

The Eyak were organized into two moieties, meaning their clan system was divided into two reciprocating halves or “one of two equal parts.” Their moieties, Raven and the Eagle, equated with the Tlingit Raven and Eagle/Wolf and with the Ahtna Crow and Sea Gull moieties. The names and stories of the clans in these moieties showed relationships with the Tlingit and Ahtna.

In the Tlingit clan system, one moiety was known as Raven or Crow, the other moiety as Eagle or Wolf depending upon the time period. Each moiety contained many clans. The Haida have two moieties, Eagle and Raven, and also have many clans under each moiety. The clans that fall under the Haida Eagle would fall under the Tlingit Raven.

CLOTHING and Regalia

All four groups used animal fur, mountain goat wool, tanned skins, and cedar bark for clothing. Hats made of spruce roots and cedar bark kept the rain off the head. After western trading, wool and cotton materials were common.

Regalia worn at potlatches included the Chilkat and Raven’s Tail woven robes, painted tanned leather clothing, tunics, leggings, moccasins, ground squirrel robes, red cedar ropes, masks, rattles, and frontlets. Other items used at potlatches include drums, rattles, whistles, paddles, and staffs. Only clan regalia named and validated at a potlatch could be used for formal gatherings.

The Chilkat robes are made of mountain goat wool and cedar warps. The Chilkat weaving style is the only weaving that can create perfect circles. The Raven’s tail robe is made of mountain goat wool. Some of the headpieces had frontlets that would also have sea lion whiskers and ermine. After contact, robes were made of blankets, usually those obtained from the Hudson Bay trading company, adorned with glass beads and mother-of-pearl shells, along with dentalium and abalone shells.

TRANSPORTATION

The main mode of travel was by canoe. The people traveled regularly for seasonal activities such as subsistence and trading. The Haida canoes, made from a single cedar log up to 60 feet in length, were the most highly prized commodity.

TRADITIONAL SUBSISTENCE PATTERNS

Contemporary subsistence activities and traditional ceremonies are still essential and important to the Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian Peoples' cultural identity. The water supplied their main food. One of the most important fish is salmon. There are five species: King (chinook), silver (coho), red (sockeye), chum (dog salmon), pink (humpback or humpy). Steelhead, herring, herring eggs, and hooligan (eulachon) were also caught and eaten.

Southeast waters produce an abundance of foods, including a variety of sea mammals and deepwater fish. Some sea plants include seaweed (black, red), beach asparagus, and goose tongue. Some food resources are from plants (berries and shoots), and others come from land mammals (moose, mountain goat, and deer).

Traditionally, clans owned the salmon streams, halibut banks, berry patches, land for hunting, intertidal regions, and egg harvesting areas. As long as the area was used by the clan, they owned the area. The food was seasonal and therefore had to be preserved for the winter months and for early spring. The food was preserved by smoking in smokehouses or was dried, either by wind or sun. These subsistence patterns are still a crucial part of Southeast Alaska Native Peoples' cultural identity.

CEREMONIAL / BELIEFS

The Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian are known for a ceremony called the “potlatch” and feasts. Potlatches are formal ceremonies. Feasts, a less formal but similar event, are more common with the Haida, in which debt was paid to the opposite clan.

EVENTS

High-ranking Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian clans and/or individuals were expected to give potlatches. However, a potlatch could be given by a commoner who could raise his position by doing so. Except in the Haida tradition, the host would not raise his personal status, but rather the status of his children. Potlatches were held for the following occasions: a funeral or memorial potlatch, whereby the dead are honored; the witness and validation of the payment of a debt, or naming an individual; the completion of a new house; the completion and naming of clan regalia; a wedding; the naming of a child; the raising of a totem pole; or to rid the host of a shame. Potlatches might last days and would include feasting, speeches, singing and dancing. Guests witness and validate the events and are paid with gifts during the ceremony. In potlatches, there would be a feast; however, a feast does not constitute a potlatch.

Designed to Tell A Story: Cultural Patterns on Travel Alaska

Learn about the meanings behind the Alaska Native cultural patterns woven throughout the website.

New! Alaska Native Culture Guide

Immerse yourself in Alaska Native heritage and learn how to experience the living culture of the state's Indigenous peoples.

Travel Inspiration

#TravelAlaska

#TravelAlaska

@alaskanchev

@alaskanchev

@yleonthecape

@yleonthecape

@alaskanchev

@alaskanchev

@yleonthecape

@yleonthecape

@yleonthecape

@yleonthecape