Arts & Traditions

Alaska Native cultures are beautifully illustrated through the arts. Various Indigenous groups are known for their special talents and distinct styles of carving, beading, or weaving, or for their cultural dances, singing, and drumming.

Visitors to Alaska can experience performances of traditional music and dance, and see numerous examples of both ancient and modern Alaska Native art in villages, galleries, museums, and cultural centers.

STORYTELLING, MUSIC, & DANCE

Storytelling has been a powerful part of various Alaska Native cultures for thousands of years. Gifted storytellers share myths and legends, fables, social customs, traditions, and family and tribal histories from generation to generation, teaching the young about their own culture. Celebrations of any kind usually involve music and dancing, often done in elaborate regalia and masks that help to tell a story.

WEAVING & BASKETRY

Basketry and weaving are ancient arts that are still flourishing today. The small, very finely woven baskets of the Unangax̂, Sugpiaq, and Yup’ik peoples are beautiful and functional works of art. They are traditionally made of rye grass, a resource found in abundance in the Aleutian Islands and Southwest Alaska. Traditionally, these baskets were used to hold food — and sometimes even water! Unangax̂ and Sugpiaq weavers also created wearable objects, like spruce root hats, which served as functional items as well as reflections of the wearer's status.

Larger baskets, made of birch bark or spruce or willow root, illustrate Athabascan and Yup’ik basket weaving techniques. Modern Iñupiaq baleen baskets are based on traditional willow-root baskets. In the Inside Passage, in addition to totem carving, the Tlingit are known for a special weaving technique that allows the weaver to create perfect circles. These unique Chilkat blankets and robes, woven of cedar bark and mountain goat wool, are part of the regalia worn at potlatches and other festivals and ceremonial gatherings.

BEADWORK

Many cultural groups in Alaska practice beadwork for their regalia, jewelry, and fine arts. Perhaps the best known is the intricate beadwork created by Athabascan artists in Interior and Southcentral Alaska who have created beautiful beaded clothing and moccasins, belts, jewelry, and other decorative objects for centuries. Traditionally, they used seeds, carved wooden beads, shells, and porcupine quills. Glass beads were introduced after European contact.

The Unangax̂ and Sugpiaq people of Southwest Alaska also create beautiful and functional beaded headdresses (nacaq) and hunting hats, symbolizing status, wealth and ability.

CARVING

Carving, as an art form, reflects the close ties that Alaska Native cultures maintain with the environment. The materials used come from the land, and the images usually represent animals, spirits, or places.

Masks, used in ceremonies by all Alaska Native cultures, represent animals, people, birds, and fish. Carved in wood and bone, many masks are decorated with feathers, shells, and other materials.

The Iñupiaq from Alaska's Arctic region are known for their smaller carvings, frequently of animals or birds, made of ivory, whale bone, baleen, and soapstone, while the Yup’ik and Cup’ik of western Alaska make intricate dolls and carved miniatures representing various aspects of Yup’ik and Cup’ik life.

Perhaps most iconic of Alaska Native carvers are the Tlingit. Their art is displayed most prominently on totem poles, but can be seen on canoes, wooden tools, ceremonial staffs, rattles, masks, boxes used for cooking and storage, and screens used to divide living quarters in a house.

The Tlingit carve totems on poles for a variety of purposes. Totem poles in front of houses identify the clan’s history. Totem poles are also carved to depict stories, to commemorate an event, or to honor a deceased loved one or chief.

Beginning in Ketchikan and extending north throughout many of the communities along the Inside Passage, totem art can be found in galleries and ancient totems tower among the trees and rest in museums. Sitka is home to Sitka National Historical Park, which boasts a collection of totems near the visitor center and along the walking trail. Ketchikan has the Totem Heritage Center, which houses 33 totems from Tlingit and Haida villages. The center is a national landmark and is the largest such collection in the United States.

FESTIVALS

Feasts and ceremonial gatherings have always been integral to Alaska Native cultures. These are often occasions of both social and economic importance to the community. Although certain practices are unique to specific cultural groups and regions, many ceremonial traditions are common to all Alaska Native communities.

Typically, these gatherings involve dancing and singing, feasting, a gift exchange, and the wearing of cultural regalia, which might include elaborately ornamented tunics or robes, intricate headdresses or masks, and jewelry or tattoos and body paint, depending on the traditions of the particular culture.

The feasts and ceremonies are usually held in community houses, such as the Iñupiaq qasgiq. Traditionally, many occurred during late fall and early winter, after the necessary food had been gathered and stored and before the winter solstice, “when the sun sits down.” The Messenger Feast, or Kivgiq, of the Iñupiaq is an example of a festival that was an opportunity for distant kin to reestablish ties as well as to exchange gifts and trade for food or materials not easily available nearby. Different Iñupiaq groups took turns hosting the feast, which was held in early winter.

Learn more about Alaska Native festivals and cultural events.

HONORING ANIMAL SPIRITS

Community celebrations were — and still are — held to honor the spirits of animals killed in the hunt. Alaska Natives share a belief in the reincarnation of both people and animals. By honoring the animal spirits, they hope to ensure success in future hunting seasons.

The Cup’ik traditionally held a “bladder festival” every year in November or early December. They believed that the spirit of the seal lived in the seal's bladder, and hunters would carefully remove and store the bladders of the seals they killed throughout the season. After the festival, the seal spirits were returned through the ice to the sea, so they would come back the following year.

In Arctic Alaska, the Nalukataq whaling festival is held by the Iñupiaq people in spring following a successful whaling season to appease the spirits of deceased whales so that they will return in the form of new whales the next season. In addition to dancing, singing, and food, the whaling festival includes a tradition familiar to some visitors — the blanket toss. While it's now conducted as entertainment, it didn’t originate that way. An Iñupiaq hunter would be tossed in the air, enabling him to see across the horizon to hunt game. During today's celebrations, thirty or more Iñupiaq gather in a circle, holding the edges of a large skin made from walrus hides, and toss someone into the air as high as possible. The person being tossed throws gifts into the crowd and loses their turn when they lose their balance. The object: to maintain balance and return to the blanket without falling over.

POTLATCHES

While associated primarily with Tlingit, Haida, and other peoples of the Northwest Coast, potlatches are held by many Alaska Native cultures. These large gatherings may be given for a variety of occasions — a memorial for a deceased relative, a naming ceremony for a child, the completion of a new house or of clan regalia, a wedding, or the creation of a totem pole. A potlatch might also be held to rid the host of a shame or to elevate his status or that of his children. The feasting, singing, and dancing may last many days. Guests are invited to witness the event and are given gifts at the end of the celebration.

GAMES

The World Eskimo-Indian Olympics (WEIO) Games began in 1961 as an attempt to revive traditions found in rural Alaska. These games celebrate physical skills Alaska Native people need to survive in the Arctic such as the Nalukataq (blanket toss), the scissors broad jump, the two-foot high kick, one hand reach, Alaska high kick, seal hop, ear pull, knee jump, and many more.

Today, the games are a mainstay on the calendars of Alaska Native people throughout the state. Thousands of athletes, families and friends – as well as visitors – gather each summer in Fairbanks to watch the games. And while WEIO is very much an athletic competition, you’ll also find Alaska Native arts and crafts for sale, witness the powerful drumbeat of ancient song and dance, and glimpse the social fabric that holds Alaska’s Native people together.

LOOK FOR THE SILVER HAND

Handcrafted items found in galleries and shops of Alaska Native artwork make very special gifts and are a wonderful way to remember your trip to Alaska. Be sure to look for the “Silver Hand” emblem when you shop: it’s a guarantee that the piece you want was made by an Alaska Native craftsperson or artist. The “Made in Alaska” symbol ensures that the piece was in fact crafted here, and, wherever possible, made with local materials.

Designed to Tell A Story: Cultural Patterns on Travel Alaska

Learn about the meanings behind the Alaska Native cultural patterns woven throughout the website.

New! Alaska Native Culture Guide

Immerse yourself in Alaska Native heritage and learn how to experience the living culture of the state's Indigenous peoples.

Travel Inspiration

#TravelAlaska

#TravelAlaska

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

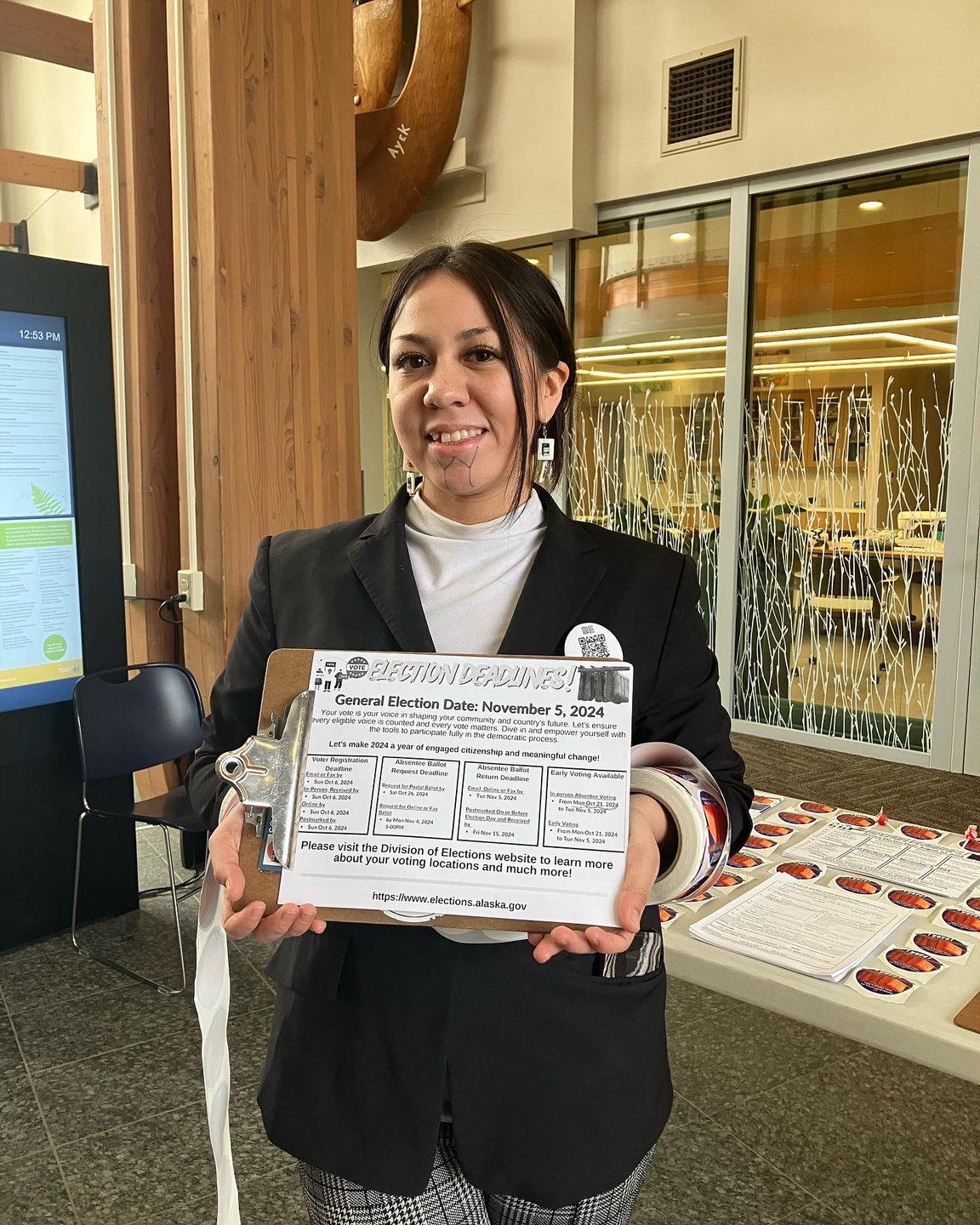

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_