Alaska's Wildlife

Alaska is where the wild things are, and the state’s incredible wildlife is as diverse as its landscapes. People travel from around the world to view Alaska’s Big 5: bear, moose, Dall sheep, wolf, and caribou, along with impressive marine mammals like humpback whales, orcas, and gray whales.

Other types of wildlife are less common, but all the more exciting for their rarity. Alaska's broad, uninterrupted swaths of wilderness are home to animals like lynx and wolves that are usually so shy, even locals are thrilled to catch a quick glimpse. And don't forget about the smaller animals: from wood frogs with antifreeze in their veins to the tiny collared pika, Alaska's smallest year-round inhabitants have made astonishing adaptations to living in this northern climate.

While we can’t cover all of Alaska’s animals both large and small, here are just a few of the top Alaska animals and where you can see them:

BLACK BEARS

Black bears are the smallest of Alaska’s three bear species (the other two are grizzlies and polar bears) and have a pointier snout than grizzlies. Black bears aren’t always black, as strange as that may seem. Colors vary from white or creamy to brown or cinnamon. The state is also home to rare “glacier” bears, with silver-blue fur, found near Yakutat and sometimes elsewhere in the Inside Passage. Black bears spend their summers fattening up on salmon and berries and can put on hundreds of pounds over a few months. Several designated bear viewing areas around the state offer a safe and fascinating vantage for watching bears as they eat, play, and raise their babies.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Black bears live in most of Alaska’s forested regions, from the southernmost tip of the Inside Passage to well north of the Arctic Circle and nearly the entire east-west width of the state. Visitors hiking the trails of Southeast and Southcentral Alaska should always make plenty of noise to avoid startling bears. Bears will usually leave you alone as long as they know you’re coming.

Best areas to view black bears: Pack Creek Bear Viewing Area, Anan Creek Wildlife Observatory Site, and other areas in Tongass National Forest

Black bears hibernate in the winter, so you won’t see them then. Generally, they hibernate in fall and come out in spring. In some of the southernmost areas, they may emerge during a warm winter, whereas in the Arctic, they can hibernate for seven to eight months.

BROWN BEARS

Brown bears are much bigger than black bears, and seen side-by-side, it’s easy to tell them apart. While both species come in a variety of colors, from black to light brown, brown bears are distinguishable from black bears by the larger hump on their back and smaller ears.

Brown bears that live in non-coastal areas are typically slightly smaller than their coastal cousins and are also called grizzlies. Coastal brown bears are typically larger than grizzlies because of their access to salmon and other food.

Brown bears on Kodiak Island are classified as a distinct subspecies from those on the mainland because they are genetically and physically isolated. They even look different than their mainland relatives — the shape of their skulls is different, and they tend to be larger on Kodiak Island, lending this subspecies its mythic reputation. Kodiak brown bears are among the largest bears in the world – matched only in size by polar bears – weighing up to 1,500 pounds and standing up to 10 feet tall.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Brown bears are found throughout Alaska, and it’s easier to say where they aren’t found than where they are. They aren’t on the islands south of Frederick Sound in the Inside Passage, the islands west of Unimak in the Aleutian Chain, or the islands of the Bering Sea. They are often spotted swimming from island to island, particularly in the Inside Passage, fishing along streams and rivers, and rooting for berries, bugs, and small mammals along mountainsides.

Best areas to view brown bears: Katmai National Park & Preserve, Lake Clark National Park & Preserve, McNeil River State Game Sanctuary, Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, Pack Creek Bear Viewing Area

Brown bears hibernate from five to eight months in dens. In areas with warmer winters like Kodiak Island, a few bears may stay active all winter. Pregnant females are usually the first to enter dens in the fall, and with their newborn cubs, are the last to exit dens. Adult males, on the other hand, appear to enter dens later and emerge earlier.

MOOSE

Moose are among the most popular photographic subjects in Alaska, and many people are surprised at how large they are. Males, or bull moose, can weigh up to 1,600 pounds and stand over six-and-a-half feet tall at the shoulder. Babies, called calves, usually stand within a day of birth, though their long, spindly legs make them fairly awkward. They are about 30 pounds at birth and can grow to 300 pounds or more within five months. Moose are the largest members of the deer family, and the moose found in Alaska are the largest in the world.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Moose are the most commonly seen of Alaska's "Big 5," with around 200,000 in the state. They range from the Inside Passage all the way up to the Arctic and are most abundant in the Southcentral and Interior regions. Though they are often spotted in wilderness areas, they can also be seen in cities like Anchorage and Fairbanks.

Best areas to view moose: Southcentral and Interior regions, Denali National Park & Preserve, Chugach National Forest, Chugach State Park

Moose can be seen all year long. They are commonly seen in cities during the winter, when their main winter food source – twigs – are harder to get to in the deeper snow in dense woods and at higher elevations. The scarcity of food in the winter causes moose to lose a lot of weight during Alaska’s longest season, and in the summer they are busy eating almost constantly to fatten up to get through the next winter.

CARIBOU

Caribou are a member of the deer family and look a lot like their close relatives, the reindeer. Unlike other members of the deer family, both male and female caribou grow antlers, though males grow larger antlers than females. Both male and female caribou develop “velvet” on their antlers — an extra-soft layer of fur that they shed annually. Caribou migrate in large herds, and if they decide to cross a highway, it can take a long time to get where you want to go. While this is unusual, it is quite a spectacle.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Caribou live in the tundra and forests in the Arctic, Southcentral, Interior, and Southwest regions of Alaska. There are around 750,000 caribou in the state in 32 distinct herds, with some herds of over 200,000 animals.

Best areas to view caribou: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Gates of the Arctic National Park, Denali National Park & Preserve, Kobuk Valley National Park

Caribou can be seen any time of the year. Caribou are migratory and can move up to 50 miles per day. They tend to use the same migration routes year after year, though they can abandon those routes in favor of new areas with more food.

DALL SHEEP

Dall sheep are distinguished by their curled horns. Male Dall sheep (called rams) can grow particularly large racks called “full curls,” meaning they have an entire 360-degree turn in their horns. Both male and female Dall sheep grow horns, but females (called ewes) grow smaller horns. They are agile and skilled at climbing steep, mountainous terrain.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: One of the most popular places to see Dall sheep is along the Seward Highway south of Anchorage. They are found many other places, but not usually so close to a major highway. The Alaska Railroad runs along the highway in this area, and the glass-domed cars on the train make for an excellent vantage point. Dall sheep inhabit mountain ranges primarily in Southcentral, Interior, and Arctic Alaska, often perched on rugged, steep slopes and ridges.

Best areas to view Dall sheep: Southcentral and Interior regions, Denali National Park & Preserve, Chugach National Forest, Brooks Range, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park

Dall sheep can be seen any time of year. But because of their white color, it’s much easier to spot them during the summer, when the brown and gray rocks contrast nicely with their coats.

WOLVES

Wolves are pack animals and their pack behavior is dictated by a highly structured hierarchy. Packs average around six to seven animals, and fighting within the pack is rare unless the animals are stressed or having a hard time finding food. It is uncommon to spot a wolf in Alaska, not because they aren't here - the state is home to 7,000 - 11,000 wolves - but because they avoid people as much as they can. You will rarely see them along a highway or on a hiking trail. If you see a wolf while boating along coastal waters or taking a wildlife tour, consider yourself very lucky.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Wolves can be found in every region of Alaska, covering a range of about 85% of the state. While they have a wide range, they are rarely seen.

Best areas to view wolves: Denali National Park & Preserve, Katmai National Park & Preserve

Wolves can be seen in winter or summer by those willing to spend the time quietly watching for them in remote areas in national parks or other protected areas.

BALD EAGLEs

Alaska is home to the densest population of the United States' national symbol - the bald eagle. Over 30,000 bald eagles live in Alaska, thriving on the abundance of fish, their main food source. The distinctive white head is easily spotted among the dense, dark Sitka spruce of Alaska’s coastal regions, and eagles are frequently seen flying above coastal waters, diving and catching fish, which they devour on shore. Bald eagles are impressively large — their wing spans can reach seven and a half feet. In certain areas, seasonal fish runs attract thousands of bald eagles at one time.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Bald eagles are most commonly seen in Southcentral Alaska and the Inside Passage region. In the Inside Passage community of Haines, eagles are attracted to a late-season run of salmon, and gather by the thousands in November and December along the Chilkat River. Farther south along the Inside Passage, the Stikine River near Wrangell hosts a similarly huge concentration of eagles in the spring.

Best areas to view bald eagles: Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve, Chugach National Forest, Kenai Peninsula, Tongass National Forest, Prince William Sound

Although the best places within Alaska to view eagles varies somewhat by time of year, eagles can be seen all year long.

HUMPBACK WHALES

Humpback whales are common sights in the summer in Alaska. The “flukes,” or tails, of humpbacks have distinct patterns that make it possible to identify individual whales. The most impressive humpback sightings involve “breaching,” when whales leap out of the water. Scientists are unsure why whales breach and have numerous theories on the matter, from pure fun to a form of communication. Another exciting humpback behavior is bubble net feeding, where groups of whales swim upwards while releasing columns of bubbles to trap small fish and krill. They then open their gigantic mouths at the surface of the water, taking in huge quantities of water and food, and then use their baleen as a filter to push out the water.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Humpback whales spend their winters in the warm waters of Hawaii and then migrate to Alaska in the summer to feed in the state's nutrient-rich waters. The best places to spot humpbacks in Alaska are the coastal areas in the Inside Passage, Southcentral, and Southwest regions.

Best areas to view humpback whales: waters outside of Juneau, Sitka, and other Inside Passage communities, Kenai Fjords National Park, Prince William Sound, waters around Kodiak Island and the Barren Islands, eastern Aleutian Islands.

Most humpback whales head to Hawaii during the winter, so the best time to see them in Alaska is from the late spring to the fall. Humpbacks are easy to spot. When they surface to breathe, they shoot a plume of mist and water into the air and make a short, puffing sound. Find this, and you’ll probably see their tales surface a short time later as they come to the surface and dive back down to the depths of the ocean.

ORCAs

Orcas, also known killer whales, are black and white and are distinguished by their stately dorsal fins that can grow up to 6 feet tall. Orcas are the largest member of the dolphin family and typically travel in pods of up to about 40 animals. There are three different types of orcas in Alaska, based on their prey and habitat: resident, transient, and offshore. Resident orcas feed only on fish and tend to stay near coastal areas, while transient orcas feed on marine mammals like seals, porpoises, and sea lions and have a larger range. Offshore orcas are elusive and are found primarily in the open ocean, feeding on sharks and fish.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Orcas are found throughout the marine waters of Alaska but occur most commonly in the waters of the continental shelf from the Inside Passage, along the coast of Southcentral Alaska, through the Aleutian Islands, and northward into the Chukchi and Beaufort seas.

Best areas to view orcas: waters outside of Juneau and other Inside Passage communities, Kenai Fjords National Park, Prince William Sound, Kachemak Bay State Park, waters around Kodiak Island, Aleutian Islands

GRAY WHALES

Gray whales are the first migrating whales to reach Alaska each spring. Swimming slowly from their winter breeding grounds in Mexico’s Baja California, these amazing animals have one of the longest migrations of any mammal on earth — up to 14,000 miles round trip! Gray whales are “medium sized” whales, roughly 40-50 feet long and up to 90,000 pounds — about the size of a school bus. They may look a little rough around the edges because of the barnacles and parasites on their skin.

Gray whales are bottom feeders, scooping up the silty seafloor and filtering tasty invertebrates through their baleen, so they are typically seen within a few miles from shore. They usually don't breach or spy hop in Alaska, but you may see them spout or raise their pectoral fins or flukes out of the water while they’re feeding in shallow areas. While you won’t see big pods of gray whales — they’re fairly solitary — you may see them traveling in small groups.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: From Mexico, gray whales travel up the west coast of the U.S. and Canada, cruising along the Inside Passage and Gulf of Alaska, ultimately heading through False Pass in the Aleutian Island chain to their summer feeding grounds in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas.

Best areas to view gray whales: Kenai Fjords National Park

The best time to see gray whales is during the migration, before and after they reach their northern feeding grounds. You may start seeing gray whales heading north along Inside Passage and Southcentral waters in March, then again as they and start swimming south in October. Many whale watching tours start operating in early spring to catch the northward migration.

PUFFINS

Puffins are one of the most distinctive sea birds in coastal Alaska. Both varieties found in Alaska — the tufted puffin and the horned puffin — feature bright-orange beaks and webbed feet with black-and-white coloring. Early sailors called them “sea parrots” because of this color scheme. The tufted puffin is named for the golden tufts of feathers behind each eye, while the horned puffin is named for the black horn-like markings over each eye. Their average wingspan is 25–30 inches and they weigh about 1.5 pounds.

Puffins are built for swimming underwater rather than for flying, and the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward, a wildlife rescue, rehabilitation, and education center, allows visitors to watch puffins and other seabirds dive to the bottom of their multi-level seabird enclosure for food. When they dive, puffins flap their wings through the water, appearing to fly. After they scoop the food off the bottom, they simply point their beaks toward the surface and slide up through the water.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Puffins are found in the Inside Passage, Southcentral, and Southwest Alaska along the coast. The best way to see puffins is on a wildlife cruise or kayaking trip departing from coastal communities like Seward, Valdez, and Kodiak. Your best bet for up-close views of puffins is at the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward, where you can join a Puffin Encounter tour and go behind the scenes to meet and feed the center’s resident puffins.

Best areas to view puffins: Kenai Fjords National Park, Prince William Sound, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, waters around Kodiak Island

Puffins spend May through September in rookeries along the coast, nesting in dirt burrows or in notches in the rocky coastline. Here, each breeding pair raises one baby per season, tending the egg until around July, then carefully guarding the delicate baby until fall, when it is capable of feeding itself. Puffins tend to spend the winter at sea in the North Pacific Ocean.

SEA OTTERS

This little creature has played a big role in the modern history of Alaska. Although sea otters range as far south as California, early explorers had never seen them in such abundant quantities as they did in Alaska. Pelts brought to Russia after Vitus Bering’s 1742 voyage to Alaska prompted the Russians to sail to Alaska and set up fur-trading settlements throughout Alaska’s southern coastal region. The otters were hunted to near-extinction, but a treaty signed in 1911 marked the end of their decline. Sea otter populations in Alaska are now quite healthy.

Sea otters are not related to seals or sea lions, but are rather a member of the weasel family. Unlike seals, they stay warm in Alaska’s cold waters not with a thick layer of blubber but with dense underfur that traps air bubbles to keep them afloat and prevent them from becoming totally soaked. This adaptation is key to their survival, so they spend a lot of time grooming. They can be seen linking arms or floating together in large groups called "rafts."

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Sea otters are seen from the Aleutian Islands, across the Kenai Peninsula and the Gulf of Alaska, and south to the Inside Passage. They tend to stick together in small communities and don’t range far unless food becomes scarce. They are curious animals and quite gregarious. They are often seen floating on their backs, cracking open mussels or other shellfish on a rock to get at the tasty insides.

Best areas to view sea otters: Coastal areas along the Inside Passage, Prince William Sound, Kenai Fjords National Park, Kachemak Bay State Park, waters around Kodiak Island, Aleutian Islands

Sea otters are found year-round in Alaska’s coastal areas.

MUSKOXEN

Muskoxen are prehistoric-looking animals with long coats that skim the ground and horns that curl toward their faces. They don’t just look prehistoric: it is believed that the ancestor of the muskoxen migrated to North America between 200,000 and 90,000 years ago. The underhair of muskoxen is called qiviut, and it is softer than cashmere. Muskoxen living in captivity are groomed for this prized underhair. In numerous Alaska Native villages, women knit the qivuit into scarves, hats, and other crafts that are warm, soft, and water-resistant. Each village has a particular pattern, and these items are highly prized. A cooperative of qivuit knitters in Anchorage called the Oomingmak Cooperative sells hand-crafted items from a small retail shop, or you can find qivuit items in a number of other gift shops statewide.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: There are about 4,000 muskoxen in Alaska, and they are found in very specific places: the northeast and northwest Arctic, western Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Seward Peninsula in the western Arctic, Nunivak Island, and Nelson Island. In the summer, they gravitate toward river valleys to feast on sedges and grass, and in the winter they move to higher ground to avoid deep snow.

Best areas to view muskoxen: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge

Muskoxen can be seen year-round. They are usually found in herds, and with their long coats, appear to be hunkering down in the cold wind and snow.

POLAR BEARs

Polar bears are one of the largest bears in the world, matched only in size by the massive Kodiak brown bears on Kodiak Island. Polar bears can weigh over 1,500 pounds and stand up to 10 feet tall. Unlike brown bears, polar bears are strictly carnivorous and live nearly their entire lives on sea ice. They have waterproof guard hair to keep them warm and dry when they’re swimming, and also have hair between their toes and pads on their huge feet. They can be dangerous animals that are only found in remote Arctic regions and should only be viewed with an experienced guide.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Polar bears are most abundant near coastlines and toward the southern edge of the ice pack in polar regions. In Alaska, they can be found in the northern Arctic and Western Arctic areas, usually on the frozen sea, but sometimes on land near towns like Kaktovik, Utqiagvik, and Kotzebue. Polar bears don’t tolerate temperatures above 50 degrees Fahrenheit because of their thick coats and metabolisms, so they prefer to stay near cold ocean waters and ice.

Best areas to view polar bears: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge through the gateway community of Kaktovik, Utqiagvik

Polar bears can be seen in Alaska usually in fall and spring on guided wildlife tours available from the remote Inupiaq communities of Kaktovik and Utqiagvik, accessible by air from Anchorage and Fairbanks. Although polar bears don’t go into full hibernation like brown and black bears, they are scarcely seen in the dead of winter. Pregnant females are the only polar bears that fully hibernate during the winter.

WALRUS

In shape, walruses look a lot like their pinniped relatives - seals and sea lions - but two major characteristics set the walrus apart: they are much larger and have gigantic tusks found on both male and female adults. In fact, the genus name for the walrus, Odobenus, means tooth-walker, and truthfully describes the great use walruses get from their tusks. Tusks can be used for climbing on both ice and land, but also come in handy for fighting and establishing dominance.

Animals with the largest tusks are dominant over the others, but walruses are also fiercely loyal and will not abandon injured brethren. Adult male walruses can weigh as much as 4,000 pounds, making them by far the largest of the pinnipeds, and although they are generally harmless, their great size and inquisitiveness means you should be very careful around them. Alaska Natives have long relied on walruses for food and for the many uses they get from the hide and gut. In fact, early Alaska Natives made rain gear out of the gut of walrus and covered kayaks in their hides.

WHERE & WHEN TO SEE THEM: Pacific walruses are found in the Bering and Chukchi seas, from Bristol Bay in Southwest Alaska to Point Barrow near Utqiagvik in the Arctic.

Best areas to view walrus: Walrus Islands State Game Sanctuary, Pribilof Islands, St. Lawrence Island

The easiest time to see walrus is in the summer, though they are around all year long.

Alaska: AKA Your Next Adventure

Where will your Alaska adventure take you? Order our Official State of Alaska Vacation Planner and plot your course.

Travel Inspiration

#TravelAlaska

#TravelAlaska

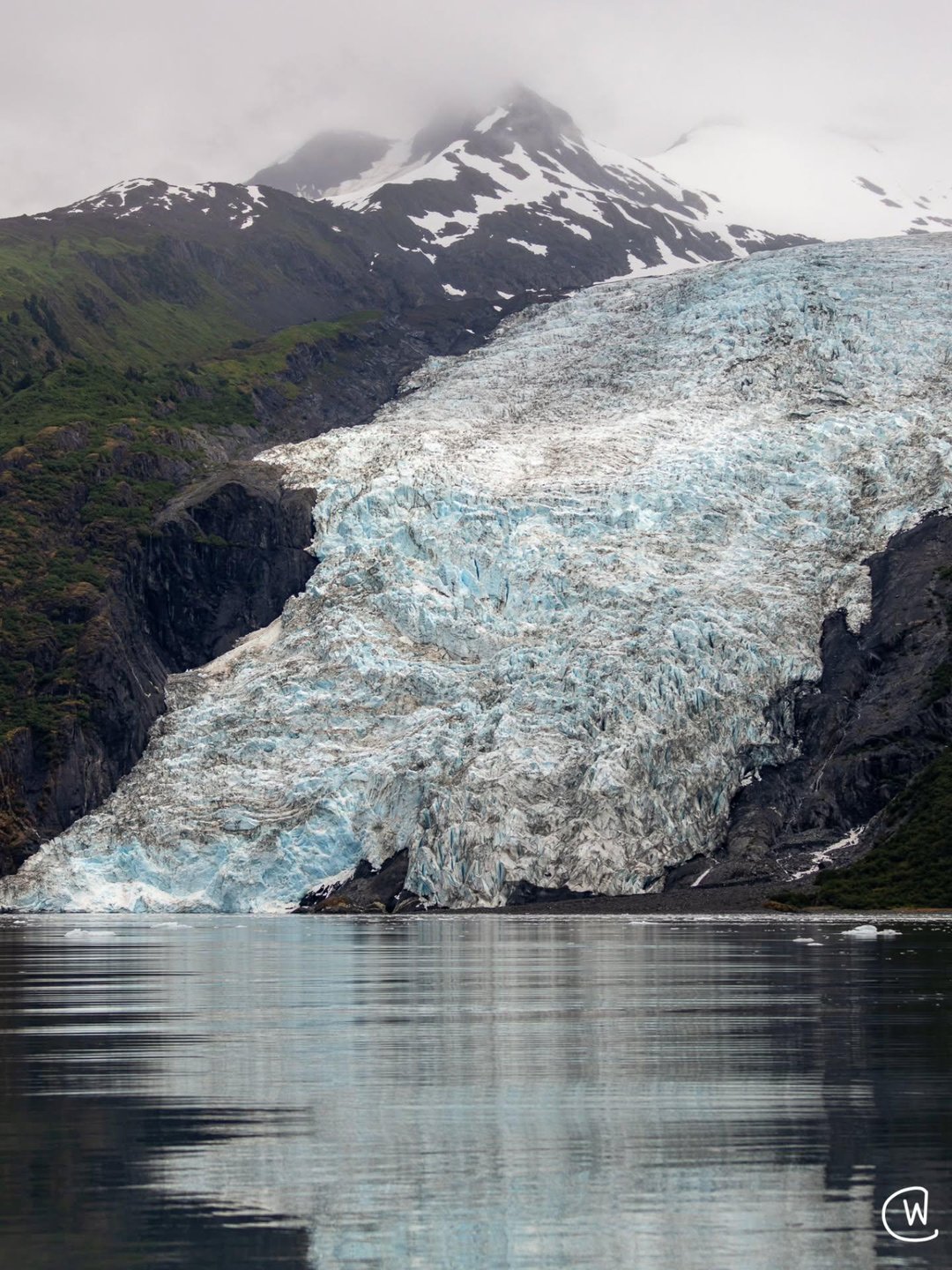

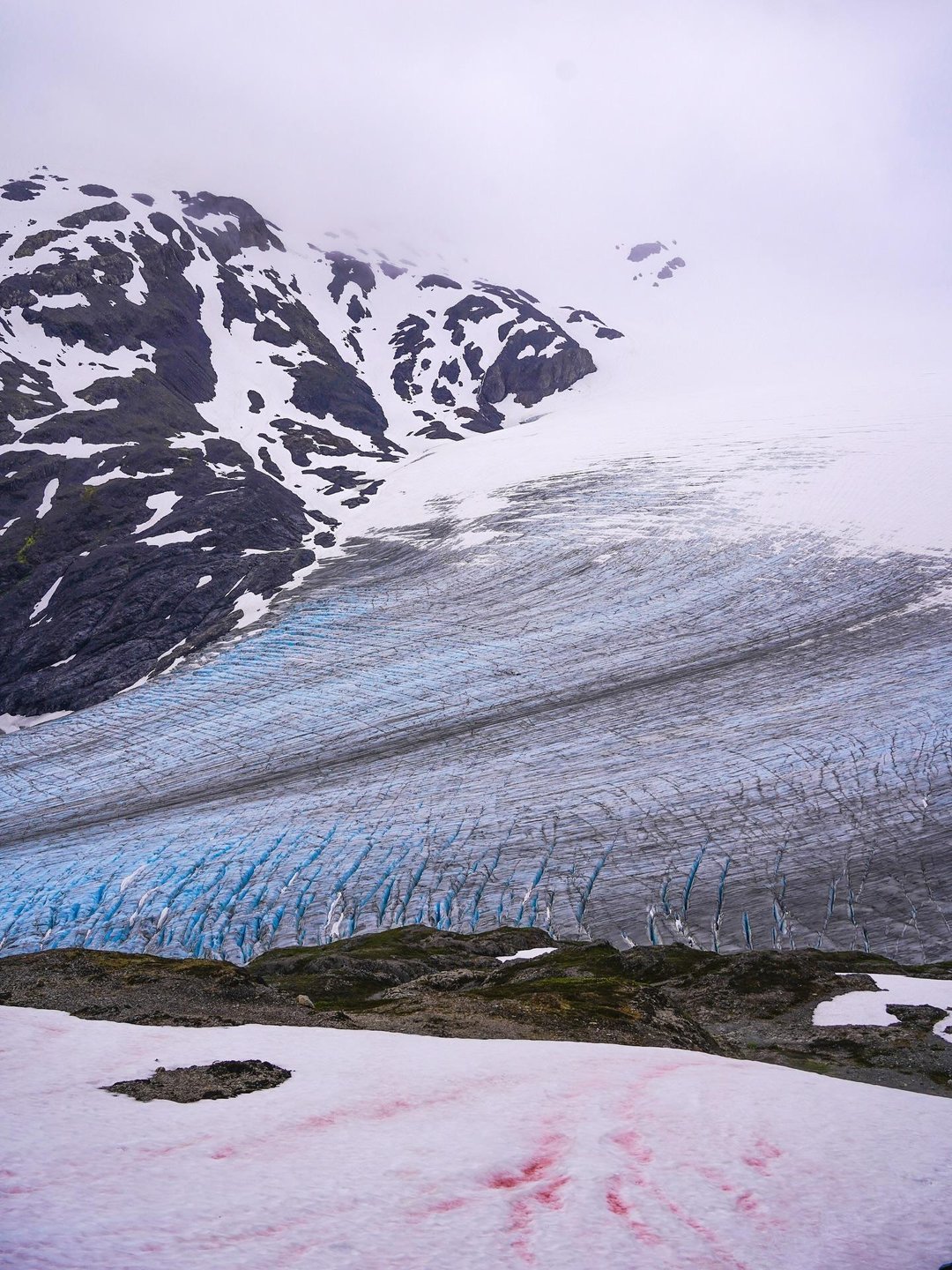

@cw.photo406

@cw.photo406

@j.hunter_photo

@j.hunter_photo

@cw.photo406

@cw.photo406

@cw.photo406

@cw.photo406

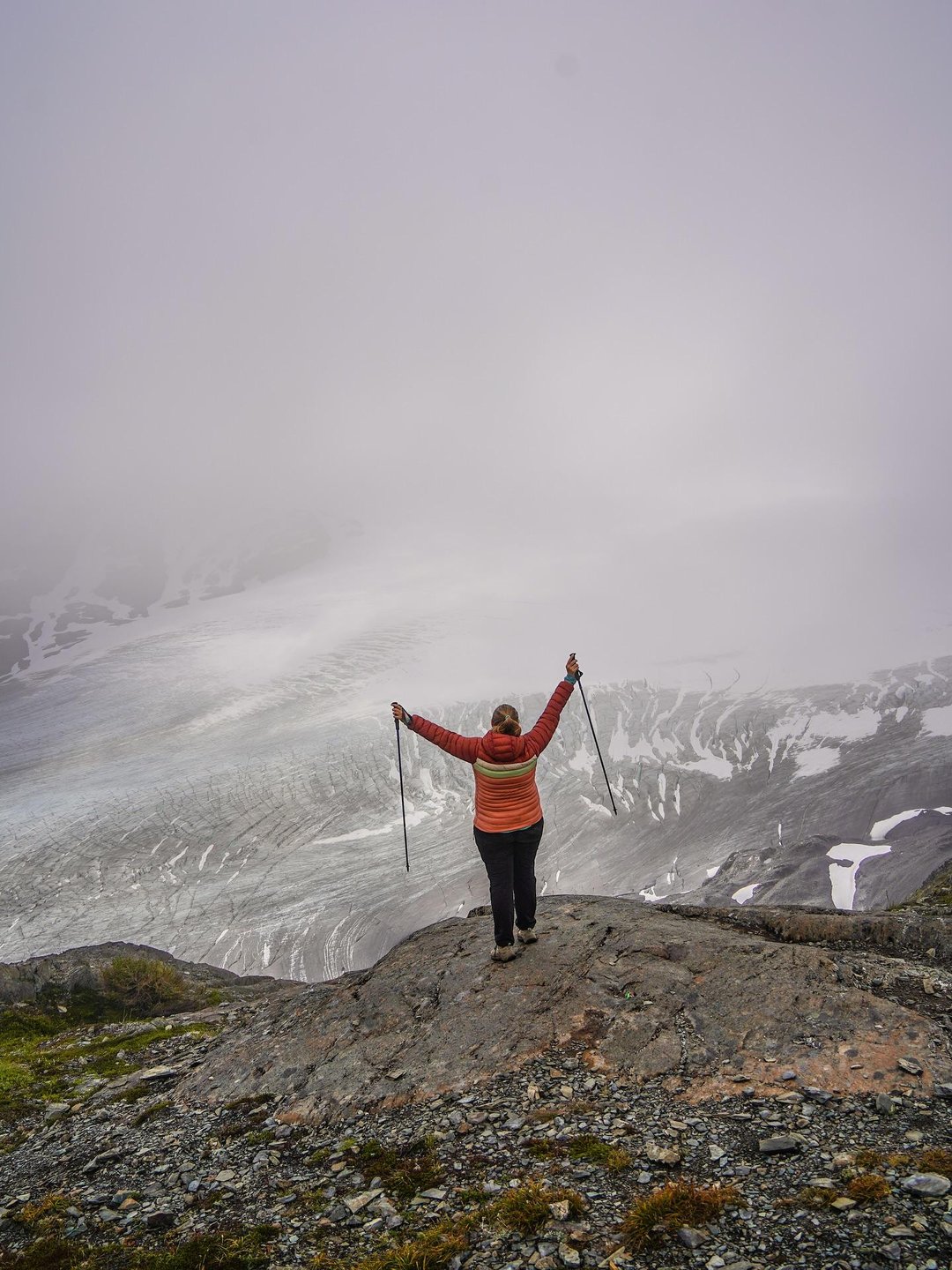

@lostwithlydia

@lostwithlydia