Yup'ik & Cup'ik Culture

Yup'ik and Cup'ik Alaska Native peoples are traditionally from Southwest Alaska, including the Yukon Kuskokwim Delta and Bristol Bay area. The Yup'ik and Cup'ik rely on a subsistence lifestyle of hunting, fishing, and gathering local foods. They are known for their mask making, grass baskets, and dance fans.

Like much of Alaska, these communities are spread across a vast region. To this day, many can only be flown or traveled to by boat as the weather permits.

Storytelling through dance and oral tradition celebrates everyday activities and special events in the life of the community. Bethel hosts the popular Cama-i Dance Festival where you can see groups from all over the region and around the state perform.

Traditional housing styles and the materials used to build them vary from group to group, but semi-subterranean structures with underground tunnels for entrances were common, particularly in the more northern communities. Yup’ik and Cup’ik males old enough to leave their mothers lived with the men in a qasgiq, or men’s house, which also served as a community center. Women lived in an ena, where the cooking and child-rearing was done. Today, people live in houses, but multigenerational households are common. Instead of the qasgiq, the communities are often centered around institutions like the school or tribal halls.

Socially, villages were organized around extended family groups, and rank was determined by the skills an individual offered the community. Shamans played an important role in many villages, healing the sick and praying for good hunting or weather.

Yup’ik is one of the strongest Alaska Native languages still in use, and in many communities is still the primary language spoken. The Cup’ik language is also still in use, but the Cup’ig dialect spoken on Nunivak Island is threatened.

In Bethel, you can visit the Yupiit Piciryarait Cultural Center, where Elders share language, culture, and arts programs. The Center's collections include historic artifacts and modern designs. Found in Quinhagak, south of Bethel, is the Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Center, home to the largest collection of pre-contact Yup’ik artifacts in the world, all excavated from the Nunalleq site just outside the village.

Cultural Regions Map

Yup'ik & Cup'ik Traditions & History

From the Alaska CulturalHost Program

House Types & Settlements

Many of today’s villages (totaling 50 today) were once ancient sites that were used as seasonal camps for subsistence purposes. Historically, the Yup’ik People were mobile, traveling with the arrival of seals in the springtime, berries, and salmon in the summer, berries in the fall time, as well as numerous game and edible plants. The ancient settlements and seasonal

camps contained small populations, with numerous settlements throughout the region consisting of extended families or small groups of families.

All males in the Yup’ik/Cup’ik community lived in a qasgiq (kuz-gi), or men’s house/community center. Boys around the age of 5, when they acquired awareness and were able to follow instructions, were considered old enough to leave their mothers and joined their male relatives in the qasgiq, where they lived, worked, ate, bathed, and slept together. These first schools were important institutions of each village, where boys learned their role in the community as well as how to provide for their families.

Meanwhile, Yup’ik women prepared food for her male relatives who resided in the qasgiq. Ceremonies perpetuating the successful hunt for food, including singing and dancing were held at the qasgiq, thus making it a community center.

Women and girls lived in an ena (inna), which had architectural features similar to the qasgiq, although the qasgiq was much larger. All sod houses were made from driftwood, tundra sod, and included a seal or walrus intestine removable “skylight” window. Like most other winter dwellings, the qasgiq and the ena shared the distinctive, partially semi-subterranean winter entrance passageway—which in the ena also provided space for storage and cooking.

Once the territory required children to attend school, families settled in permanent villages, and stores, post offices soon followed. Today, many families maintain a fish camp nearby, perpetuating the harvesting of food from the water as others have done for thousands of years. The settlements that once numbered in the thousands are now hard to discern from the landscape. A collapsed sod house may be the only sign of these once robust settlements that are disappearing into the landscape.

Tools & Technology

Technology was highly adapted to survival in the sub-arctic environment, and was fine-tuned through the centuries by trial and error. Technology was mostly geared toward the harvesting of marine mammals along the coast and more riverine habitats in the delta regions, using bone, ivory, animal skin and driftwood for crafting tools necessary for survival.

Women’s important household items included the versatile, fan-shaped, slate knife called uluaq (oo-loak), stone seal-oil lamp and skin sewing implements made from stone, bone and walrus ivory. Men’s tools were associated with hunting and were elaborately decorated with specific animals, whose spirit aided in successful hunting. Hunting items included a variety of spears and spear throwers (for hunting birds, fish, seal), harpoons (for hunting whale, seal and walrus), snow goggles, fishing hooks, and bow and arrows.

With the advent of Western influence, hunting implements soon gave way to rifles. Carving masks for hanging on walls to sell are common, although some village dance groups are bringing back face masks to wear during yuraq (Yup’ik dancing). Skin boats are no longer used, replaced by gas-powered, wooden hand-made boats in the 1940s, followed by Lund skiffs and other manufactured boats. Although the tools for harvesting food have changed, the activities around hunting and fishing, berry picking, and gathering edible greens is still a vital source of nutrition for the Yup’ik People. The first fresh meat of the year is a

welcome addition to a family’s diet. Fresh seal meat and herring fish/eggs are eaten in May. Migratory birds arrive soon after, feeding families with fresh bird soup and boiled bird eggs follow. Salmon return and harvesting salmon for personal use keeps families busy throughout the summer.

Blueberries ripen in early July, followed by salmonberries, a favorite to this day. Blackberries or crowberries ripen in fall, followed by low-bush cranberries. Edible greens are harvested as early as April, when the tundra pond greens grow in shallow ponds that dot the tundra for miles. Roots of certain plants, wild celery, sourdock, and other greens are harvested in summertime. In the fall, after the first frost, sea grass or rye-grass is picked and set aside to be cured. Later on in the winter, they will be made into beautiful grass baskets. Once used for storing food, they are made to sell as gifts, often adorned with colorful designs such as butterflies.

Social Organization

Social norms and behavior were all geared toward survival and compatibility among family-village groups. Roles and social rank were largely determined by gender and individual skills. Elders, seen as the first teachers, had an important role as the head of the family unit. Babies were revered, gifted with names of the recently deceased or a family member. Successful hunters, given the title of nukalpiat (nu-gut-pat) by others, usually become group leaders. Women’s roles included child rearing, food preparation, and sewing garments for inclement weather. With the passing of ANCSA, each village is now a federally-recognized tribal entity, and Indigenous members enroll as members of that tribe. Each tribe also owns a for profit business; tribal members are shareholders who hold board elections and run businesses for the purpose of bringing money into the tribe.

Role of Shaman

Shamans played an important role in the community. Considered a healer and a leader, he or she was a medical provider, a therapist, as well as someone who could interact with animal spirits during important dance ceremonies. Shamans would heal the sick in the qasgiq wearing a face mask of the animal spirit whose job it was to ‘eat’ the illness from the body. Shamans were vital for communities since he/she was vital in interacting with animal spirits, asking them to return to the people for sustenance. Shamans were not taught; rather, they were chosen by animal spirits and were given special powers early on in life. It is said that once Western Christianity arrived, shamans were considered evil by outside parties and the role of the shaman ended.

Clothing

Traditionally, skins of certain birds, fish, and marine and land animals were used to make clothing. Hunting clothes were designed to be insulated from wind and as well as waterproof, excellent for inclement weather year round. Fishskin and marine mammal intestines were used for waterproof shells and boots, the precursor to what we know as gortex. Grass was used to make insulating socks, and as a waterproof thread to sew two pieces of intestine together to make a strong seal. Qaspeqs became common when cloth was brought in. Once used to cover fur garments, the qaspeq has evolved to a piece of everyday clothing, adorned with rick rack and made with an electric sewing machine. Qaspeqs come in several styles, including the traditional qaspeq (with the skirt attached), the modern qaspeq (without the skirt) and now has morphed into a qaspeq with cowl neck, zippers and stretchy cotton sleeves. A sewer can easily support his/her family by making and selling qaspeqs online, as they come in many colors and designs, and are made for babies, kids and adults. The qaspeq can be worn during everyday wear, but is a necessary piece of clothing used for yuraqing (Yup’ik dancing). Qaspeqs are useful for berrypicking, as it covers the head and back from pesky mosquitoes. Fish cutters wear qaspeqs to protect clothing underneath from fish slime.

Trade

Coastal villages traded with the inland river villages regularly for items not locally available. Trade for seal oil in the springtime was highly desired by inland villages who usually bartered moose/caribou meat, fish, and furs such as mink, marten, beaver, and muskrat, for seal oil and other coastal delicacies such as walrus, clams, halibut, dried herring, and herring eggs. Facebook hosts many sites today that foster trade among villagers for the same foods that we have enjoyed for generations, including seal oil, seal meat, walrus meat, whale meat, berries, edible greens, musk ox, reindeer, fish, and migratory birds.

Designed to Tell A Story: Cultural Patterns on Travel Alaska

Learn about the meanings behind the Alaska Native cultural patterns woven throughout the website.

New! Alaska Native Culture Guide

Immerse yourself in Alaska Native heritage and learn how to experience the living culture of the state's Indigenous peoples.

Travel Inspiration

#TravelAlaska

#TravelAlaska

@travelingmelmt

@travelingmelmt

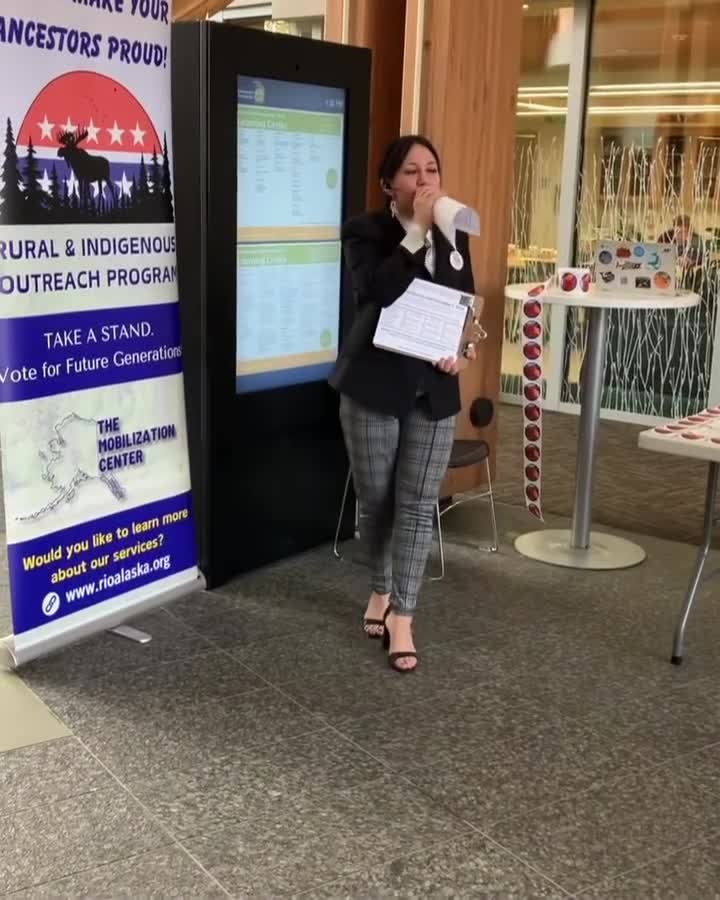

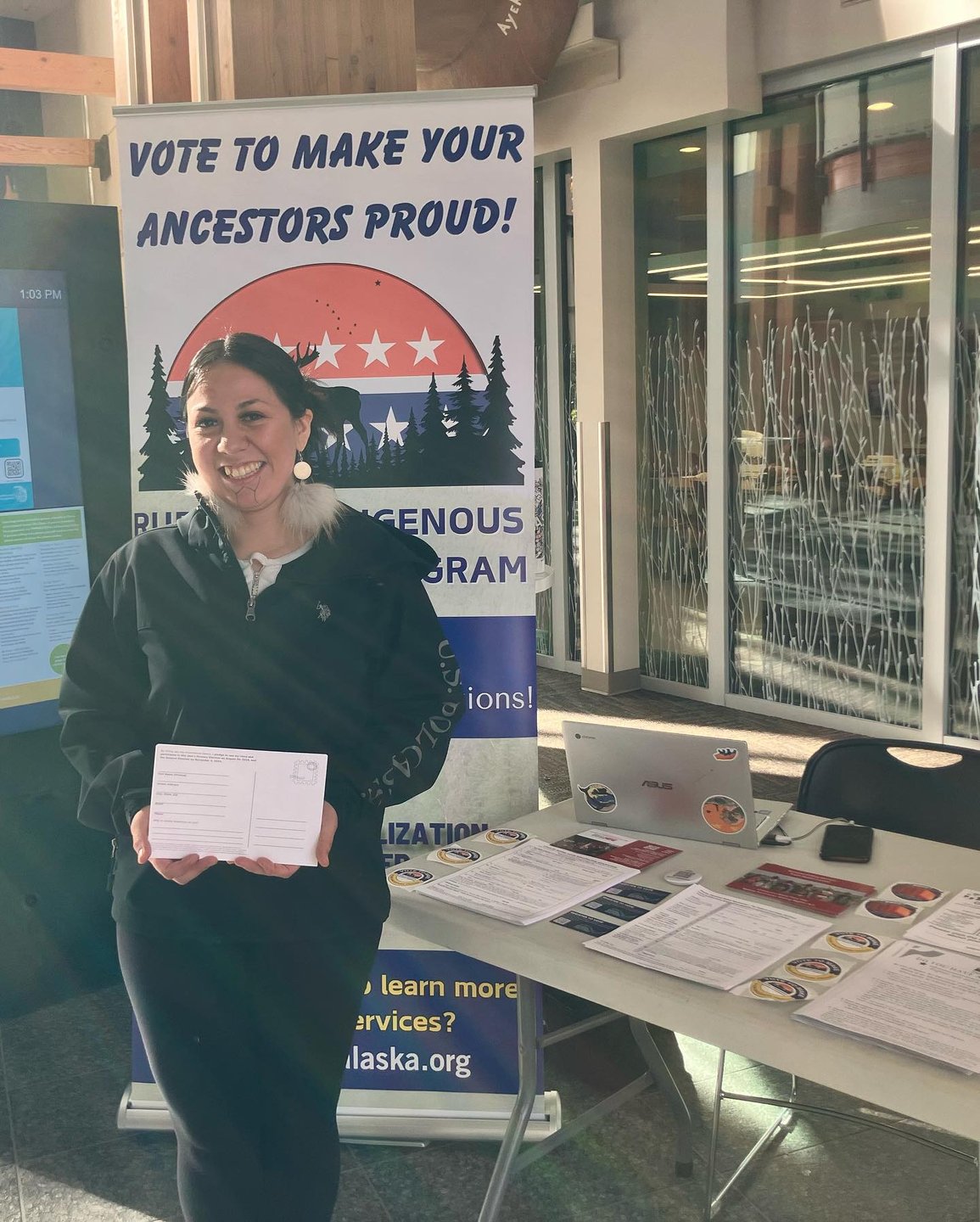

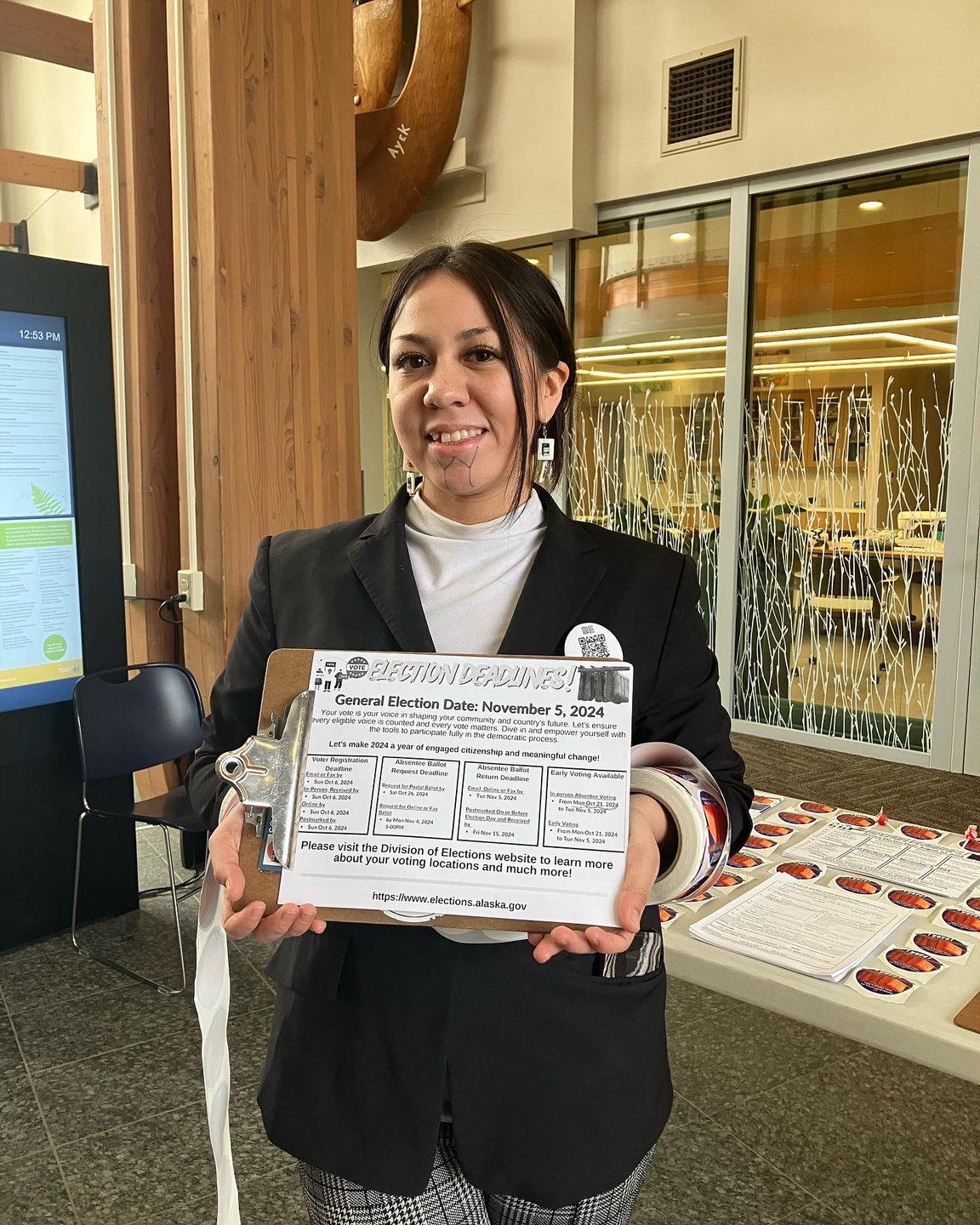

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_

@blessedbycreator_